Michael Hankard, associate professor in the Indigenous Studies department at the University of Sudbury and author of a new book, Red Dresses on Bare Trees, was initially apprehensive when he was asked by his publisher to put together a book about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Not because he didn’t have the information needed or the knowledge of the importance of such a task, but because of his gender.

Speaking on the hurt, violence and suffering that Indigenous women have faced is usually a task for other Indigenous women — or should be; those who have a true understanding of the way that not only their race, but their gender increases the likelihood that they will face violence.

Hankard spoke to grandmothers, sisters, aunties and the brave women of every community he could, and from those many conversations, one teaching — one visual — kept coming to him: an eagle trying to soar across the sky, but flying with only one wing.

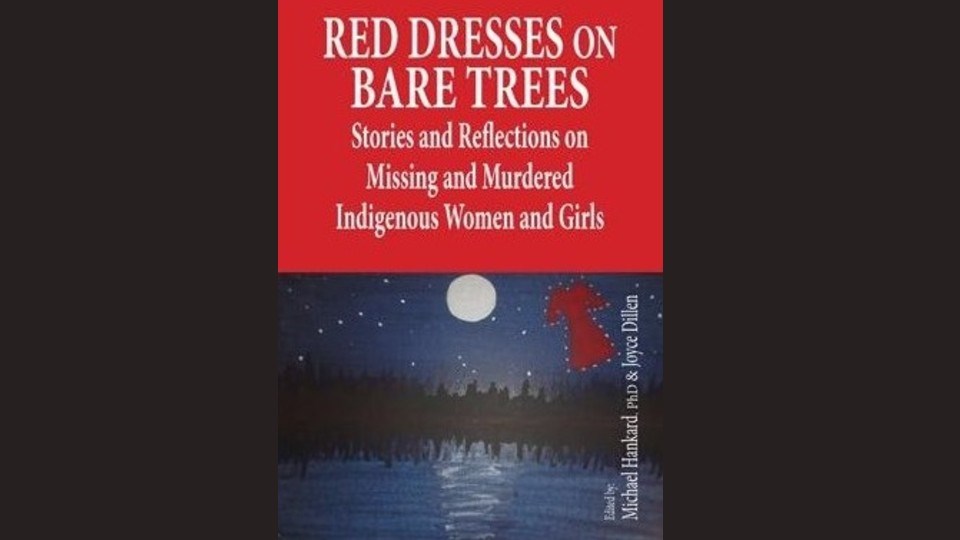

He decided to put out a call for papers to be included in the book — as well as penning his own essay and co-authoring another. The result is Red Dresses on Bare Trees: Stories and Reflections on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, edited by Hankard and Joyce Dillen, and published by J. Charlton Publishing.

Hankard is Abenaki and originally from the United States, though he has been living here in Canada for almost 20 years. In addition to his academic work, he has spent the last 25 years studying under several elders.

When he decided to undertake this endeavour and partnered with elder Joyce Dillen, it was because these teachings taught him this project was something he needed to do.

“My traditional teachings on relationships and marriage, it's all about men and women working together; it's about bringing balance and wellness,” said Hankard. “I think that we have to think about it in terms of our traditional indigenous knowledge.”

The result is a compilation of essays and reflections from both men and women, those who approach from a scientific point of view, and others who use symbolism to inform. One such piece is Hankard’s own, Walking the Sweetgrass Road Together, which has at its centre the idea that one blade of sweetgrass could never be as strong as a braid woven together — a community woven together. Even if that weave has to start with healing from violence.

The book, said Hankard, is about balance. It is also about a circle.

“I think one thing that it's important to emphasize with regard to this whole issue is going back to the traditional teachings,” said Hankard.

The description of the book itself contains the wisdom of the circle: “We begin in the eastern direction with respect — seeing someone from all sides and having ‘1,000 cups of tea’ with them; moving into time in the south where we must physically, mentally and spiritually sit and spend time with someone; then to empathy or feeling in the west where our connection to a person is strong enough that so we hurt when they are hurting; then finally into the gift of movement, where caring behaviour in the northern direction gives us drive to actually do something about it.”

“It's a personal issue. It's a family issue,” said Hankard. “If you walk that (healing) circle out further to the family, you walk it out even further to the community. And you walk it out even further to the national level. And so, it affects everybody on almost all levels, personal family, community and nation. So, it's that pervasive, that significant.”

Not only did he dedicate the book to the grandmothers he spoke with, but to the women of Serpent River First Nation, the community where Hankard has lived for 17 years.

“They’ve suffered a great deal,” he said. “There are many that have gone to the school in Spanish, but also the women that have gone missing from this community.”

Though he notes the number of women missing may seem “small” when compared to Sudbury or Toronto, it is more noticeable in smaller communities.

“The significant thing is the impact that it has on a community this size,” he said. “We have 370 people living on reserve, probably another 800 that live off-reserve; but among that community, the impacts of having even a small number of women going missing or being murdered is hugely significant. Almost everybody's related and knows who's missing - everybody is impacted by it, and everybody's traumatized by it.

And when these things happen again, says Hankard, it's re-traumatizing the community: “It's like a healing that’s never fully taken place.”

Hankard hopes that stories and reflections in the book will allow for balance and for healing, through both genders as one.

An eagle soaring through the air.

You can purchase your copy of the book at www.jcharltonpublishing.com.

Jenny Lamothe is a Local Journalism Reporter at Sudbury.com, covering issues in the Black, immigrant and Francophone communities. The LJI program is funded by the Government of Canada.